Music and Church in All Manifestations

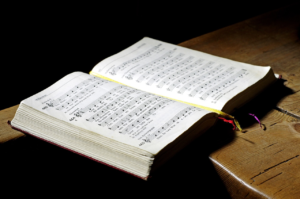

Music has always been an inseparable companion of human spirituality, and nowhere is this more evident than in the life of the church. Across centuries and cultures, church music has evolved in form and function—serving as a vehicle for prayer, a teaching tool, a bridge between the sacred and the ordinary, and an instrument of communal identity. From ancient chants echoing in stone cathedrals to modern worship bands in vibrant community halls, music continues to shape the way believers experience faith.

Religion itself is deeply personal, and public figures like Emma Watson religion conversations often highlight how faith and personal belief intersect with culture. In the same way, church music reflects not just tradition, but also the cultural values of each era. Let’s explore how music manifests in the church: as worship, as education, and as a cultural force.

Music as Worship: The Soul’s Language

The primary role of music in church has always been worship. In Christianity’s early centuries, music was closely tied to liturgy and Scripture, creating a direct line between human voices and divine presence. Gregorian chant, for example, is still admired today for its meditative quality. Its monotone simplicity invited worshippers to focus on the sacred text while simultaneously experiencing spiritual transcendence.

In Orthodox traditions, choirs without instruments emphasize the human voice as God’s purest gift. Meanwhile, in Protestant settings, congregational singing became a revolutionary form of participation. Hymns by writers like Martin Luther or Charles Wesley gave believers both poetry and melody to express devotion.

Modern churches often incorporate bands, praise leaders, and contemporary Christian music that borrow rhythms and harmonies from pop or rock. This style resonates with younger audiences, encouraging worship that feels both personal and communal. The underlying idea remains constant: music is not just art, but prayer set to sound.

Music as Teaching and Tradition

Beyond worship, church music has always played the role of educator. For centuries, when literacy was rare, hymns and chants carried theology to the people. Each verse was a small sermon, teaching core beliefs through memorable melody and rhyme.

Take the medieval period: plainchant often recited Scripture directly, allowing even the illiterate to internalize biblical passages. During the Reformation, vernacular hymns helped congregations absorb doctrine in their native tongue. Luther’s famous “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God” was more than a hymn—it was a manifesto of faith accessible to common people.

Even today, children in Sunday schools learn through simple songs that make biblical stories unforgettable. Seasonal music also preserves tradition. Christmas carols like “Silent Night” or Easter hymns such as “Christ the Lord Is Risen Today” are more than cultural staples—they are theological expressions passed down from one generation to the next.

In every era, church music has acted as a living textbook, embedding faith into the minds and hearts of believers.

Music as Cultural Expression

Church music doesn’t exist in isolation—it absorbs and reflects the culture around it. In Africa, gospel music blends Christian lyrics with local rhythms, creating worship that pulses with dance and joy. In Latin America, mariachi bands or folk styles often accompany church festivals, uniting faith with community identity.

In the United States, spirituals born in African American churches not only shaped worship but also influenced blues, jazz, and eventually rock and roll. These songs carried both spiritual hope and coded messages of resilience. Similarly, the soaring choirs of Black gospel music have become iconic worldwide, transcending denominational boundaries.

Churches also fostered some of history’s greatest composers. Johann Sebastian Bach famously described his music as being written “for the glory of God.” His sacred cantatas remain masterpieces of both theology and art. Likewise, Mozart, Handel, and Palestrina elevated worship with compositions that still echo in cathedrals today.

In the modern era, Christian pop, hip-hop, and even heavy metal bands prove that sacred music is flexible, adapting to new sounds while retaining its central purpose: connecting people to God.

Conclusion

Music in the church is not one-dimensional. It manifests as worship, education, and cultural expression—each role vital in shaping religious life. Whether through ancient chant, gospel rhythms, or contemporary praise songs, music remains the universal language of faith.

Its power lies in its ability to reach beyond words. It teaches doctrine, stirs emotion, builds community, and bridges the gap between human frailty and divine mystery. Just as discussions about Emma Watson religion remind us that faith is personal yet culturally significant, church music shows that belief is always expressed through the art and sound of its time.

In every manifestation, music continues to be the heartbeat of the church—past, present, and future.